MIAMI — These may seem to some like silly questions to ask someone like this, someone sitting in a spacious office that speaks to the spoils of victory, from the spectacular view of Biscayne Bay to a half-century's worth of hard-earned artifacts adorning the bookcases.

Yet, in light of the Miami Heat's recent losses to the roster and on the court, the inquiries seemed apropos.

Any shot that Pat Riley, team president and patriarch, has lost a little faith?

That the past nine months have shaken him?

"No," Riley said, during an hour-long interview with Bleacher Report, while nearing a 70th birthday he'd rather nobody notice, even with the book Younger Next Year prominently displayed behind him. "Just disappointed. Disappointed for Erik [Spoelstra] and for Micky [Arison] and for our fans. Really disappointed."

Suffering numerous injuries and ailments. Falling far below .500. Scrambling for an eighth seed.

"Obviously, the hit we took with LeBron [James] leaving just crushed us," Riley said. "Everybody. It just did. But I thought getting Josh [McRoberts] and getting [Luol Deng], especially those two players, to go with Chris [Bosh] and Dwyane [Wade] and Mario [Chalmers], that we could [compete]. And then, make the plan for 2016, even though I wasn't gonna wait if I could get a guy like Goran [Dragic].

"Our plan was always to move to great as quick as we could, past good. And I think that was more disappointing than anything, once we made that deal, to see what happened to Chris, which was devastating to me just from a personal standpoint. For his health. But also for the team, it was another hit."

Voice rising. Lips curling.

Not shaken. Still stirred.

"That's why it would be so great for this team, we're in this race here, if somehow we could get into the playoffs and make something of it," Riley said. "But I do think we have enough, in that in any series with anybody in the East, with what's going on in the East, that you never know. And I love that."

Yes, Pat Riley, unlikely underdog, is still fighting.

Which begs a couple more questions:

What for?

And for how long?

You can't tell the story of who Pat Riley has become or what he has come to believe, nor fully understand his ongoing persistence and defiance, without cycling back toward the beginning—if not all the way to his childhood in Schenectady, New York, where his minor league ball-playing father ordered him to always plant his feet and make a stand, then at least to the earliest stages of his NBA career.

Before all the glitz, Riley was a grunt.

That never leaves you, not even under cover of Armani.

Pat Riley (with Elvin Hayes) played for three seasons in San Diego before joining the Lakers in 1970.

A 1967 first-round pick of the San Diego Rockets out of Kentucky, he even attracted NFL interest, telling Tom Landry and Tex Schramm that he wanted to play quarterback, a request the Cowboys politely declined since they had Roger Staubach, Don Meredith and Craig Morton on hand.

Once in the NBA, Riley knew he was part of the "other half," those more like current Heat hopefuls Tyler Johnson and Henry Walker than like any of the stars he's ever acquired, those who didn't come in with all the extras, from minutes to money to credit to endorsements, those just trying to take limited talent as far as they could.

In Riley's case, reality came in the form of a finger pointed at his chest by late Lakers executive Fred Schaus, who told the guard that his only shot to stick was getting in the best shape on the star-studded squad, to make Jerry West and Gail Goodrich and Elgin Baylor sweat at practice. Riley climbed the hills, stormed the sand, did thousands of sit-ups and crunches, all precursors to the conditioning expectations he would later expect from others.

"I never lost a sprint," Riley said.

Still, it wasn't clear his career would become a marathon. Certainly not in 1975.

"For 15 years, from high school and then Kentucky and the pros, I was in this bubble, sort of protected by this bubble, and the bubble would sort of take care of you, and everything inside of the bubble would take care of you if you did what you had to do," Riley said. "And I did everything I had to do for like 15 years and then it was over with. And then I was like expelled; I was outside."

With a handful of Hall of Fame teammates in L.A., Riley found his way into the lineup by besting them in practice workouts.

He couldn't initially get a job in the NBA or in college. When he went back to The Forum, where he had won a championship three years earlier, he wasn't allowed in the family room.

"I really felt it then," Riley said.

He and his wife, Chris, coped through routine: get in the van, with its massive decorative flames, mag wheels and muffler, and head to the beach for volleyball from 9 a.m. to sundown.

"I was desperate to get back in," Riley said.

Then Chick Hearn got him a broadcasting gig.

"Ever since then, I'm here, where I am today," Riley said.

He credits his steps, the ones many fans now know by heart, to others believing in him. The nine seasons and four championships conducting Showtime as the Lakers head coach. The four seasons as Knicks head coach, once reaching the NBA Finals, though his tenure ended controversially. The two decades in Miami, most as head coach, but all as president, primary visionary and franchise face, with three titles taken.

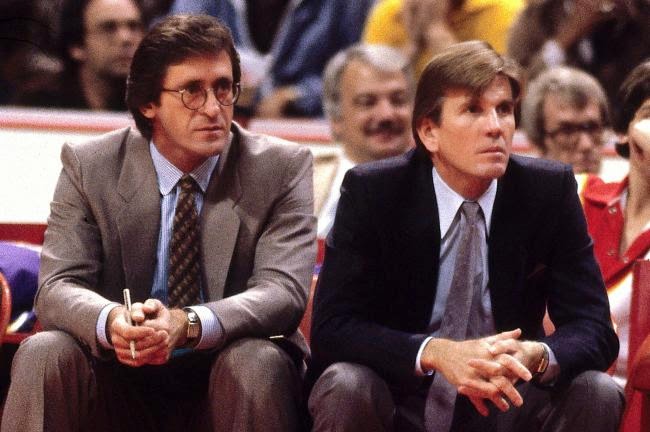

Riley spent two seasons as Paul Westhead's assistant in L.A. before taking over the head coaching duties for the 1981-82 season.

He deems some perceptions of him "mythical," especially those related to his supposedly backbreaking practices.

Sure, he asked everyone, even stars, to come fully dressed and taped prior to asking for rest, but he insists that he would alter plans to accommodate, telling them to pedal a bike just so teammates could see them participating. Yes, he typically had a three-hour window, but claims he "got 'em pretty good" for only about half of that time, while feeling that the hard work "would strengthen their muscles, their ankles, their hearts, their minds, and then in the fourth quarter, you're going to be tougher than the other team.

"Today, it's just the opposite. That would be considered harsh. It would be considered overusage. It would be what they blame you for injuries for."

Again, you need to understand where he started, even if you just go back to when he started as a head coach in 1981. Riley's first office as the Lakers head coach was a corner booth in the back of T.J.'s Coffee Shop on Sepulveda Boulevard, where he and assistant Bill Bertka would review the last game and practice plan. After players popped in for a bite, all would drive over to Loyola Marymount in their practice gear. "No showers, no locker rooms, no nothing," Riley said.

Just a clean shirt, so they wouldn't go out wet.

"So yeah, we've come a long way," Riley said.

Riley led the Lakers to four NBA championships in nine seasons on the bench in Los Angeles.

But not always for the better. He thinks some changes have created conflicts and complications: the players' personal trainers and private health practitioners; the discipline restrictions and practice limits that the players achieved through collective bargaining; the refusal of free agents to work out until signing, which he at least partly blames for their physical troubles once they come to a culture like his. He doesn't believe that the players themselves are that different these days, but "the conditions under which they play have changed dramatically."

Especially the distractions.

"There were none, it was simple, it was easy, coaching was easier," Riley said. "We live in a cyberworld. We live in a social media world. Is that a distraction? I think it is."

Players intent on expressing themselves everywhere in every moment of day and night. "All of them think that views and getting on YouTube and getting posted and all that stuff is important to their brand," Riley said. "There was none of that. It was just the game. It was the game. So there have been some changes. You have to live with them. You have to work around them."

Pat Riley has worked in three different organizations since his playing days ended, and in two very different jobs. From 1995 until 2008, with the exception of a two-year break to make way on the sidelines for Stan Van Gundy, he did both at the same time for the Heat.

Which raises another question:

Is he a better executive than he was a coach?

"No," Riley said, without hesitation. "I was a better coach. That's what I knew best."

In his final season as a coach, Riley led the Heat to a 15-67 record and the No. 2 overall pick in the NBA draft.

He measures coaches mostly by how they manage games, and all their little situations, and he thought he had come close to mastering those before he finally stepped away, and upstairs, for good. His executive role is more collaborative, with an emphasis on consensus. He praises Spoelstra, managing partner Micky Arison, CEO Nick Arison, GM Andy Elisburg and personnel men Chet Kammerer and Adam Simon for the role they play, even saying that they are ready to run things without him.

"I'm sort of the big-picture guy," Riley said.

He said he misses coaching only when he's angry, just because he sees the game the way that Spoelstra and other coaches do, from the inside-out, from the locker room to the practice court to the film room to the main court. But he doesn't envy what coaches encounter now: the overwhelming workload due to the game's computerization.

"It was very simple for me," Riley said.

He wrote out his practice plans on small cards he still keeps, dated, in office drawers. Now he sees veteran coaches like Gregg Popovich and George Karl, and "I can see what I saw on my face when I had had it. Coaching took me to a very dark place when it got bad, in 2003 and then again in 2008. When I look at what they do, and the grind and the travel, and three in the mornings, I did all that. So I don't want to do that anymore. It's not a good, healthy life. It's a life. It's a very intense, competitive life that's not really normal."

Life has generally been more balanced as an executive. He has remained true to a philosophy, one that paid off most spectacularly in 2010, after he had set the course of clearing cap space, and then played a part in convincing James and Bosh to come to South Florida and complement Wade. He doesn't bunt for base hits, but swings from the heels. He called these "very coherent thoughts and decisions that you make about getting stars. You've got to get great players. I've been around it my whole life."

"It doesn't take a rocket scientist to be able to see what it takes," Riley said, running through his experience playing with West and Baylor and Wilt Chamberlain, coaching Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and James Worthy, coaching against Larry Bird and Kevin McHale and Robert Parish, and so on. "If you can get three of those kinds of players and fill it out with some other good guys, then you might be ahead of the curve....So there are a lot of ways to skin a cat.

"For me, it's not through the draft, because lottery picks are living a life of misery. That season is miserable. And if you do three or four years in a row to get lottery picks, then I'm in an insane asylum. And the fans will be, too. So who wants to do that?"

With Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Magic Johnson, Riley saw the Lakers win 50 games for eight consecutive seasons.

No, he wants to win big, and win now, and that's exactly what the Heat did in James' four seasons in Miami. Four appearances in the NBA Finals. Two championships. The organization was where Riley wanted it, where he would have felt comfortable eventually leaving it. Then, suddenly, stunningly, it wasn't.

"That's the most surprising thing for me, is how those..." Riley said, voice rising. "Generational teams stay together. The players stay together. They know what they have. They see what they've won. They see that there's going to be a little bit of an adjustment here, and they don't want to leave that. You may never get it again.

"That was almost shocking to me that the players would allow that to happen. And I'm not just saying LeBron. I mean, the players, themselves, would allow them to get to a state where a guy would want to go home or whatever it is.

"So maybe I'm dealing with a contemporary attitude today of, 'Well, I got four years here, and I think I'll go up there for whatever reason I went.' You know, the whole 'home' thing, I understand that. But what he had here, and what he had developed here, and what he could have developed over the next five or six years here, with the same team, could have been historic. And usually teams from inside…"

Pause.

"It would be like Magic and Kareem and [James] Worthy, they weren't going to go anywhere," Riley said. "They had come at a time when there were free agents. They weren't going to go. You think Magic was going to leave Kareem? You think Kareem was going to leave Magic? You think Worthy was going to leave either one of those guys, or [Byron] Scott or [Michael] Cooper? No, they knew they had a chance to win every year. And this team had a chance every year. So that was shocking to me that it happened. Now, could we have done more? Could they have done more?"

Another pause.

"They're all hypotheticals," Riley said. "That's all they are—hypotheticals. So it did stop. And soon as it did stop, we wanted to move on as quickly as we can to try to build another one. If, in fact, that team stayed together, yeah, I probably would have retired with that team somewhere. But that isn't what I think about now."

Long after he stopped running sprints for Schaus, he's run the NBA marathon many times over.

Is a basketball life a good life?

"A great life," Riley said.

What is it about this game, even with all its misery?

"It grows on you," he said, smiling.

Still, he admitted that he's thought, at times, about taking off. About traveling even more than he does. About clearing more of his schedule for speaking and writing. About freedom.

"Freedom from," he said. "Freedom from management, freedom from responsibility, freedom from having to win, freedom from all of that which comes with being inside the bubble."

Freedom from the media, though he's already reduced his exposure plenty because "I can't stand hearing myself talk, and seeming as if [I'm] an expert on everything." Yet he acknowledged that he, like everyone else who is ambitious and achievement-oriented, does appreciate the accolades. "When you get recognition," he said, "it's cool; that's what it's about."

That recognition has largely come from winning, which he is itching to do again. He spends some time studying the depth charts and contract statuses that cover an entire wall in his office. He spends some time scouting. He spends much time cultivating relationships with player agents, communicating with other Heat officials, plotting, pondering. There was a strategy in place, and then, with James' return to Cleveland, there was a need to conceive new ones.

Riley, who feels waiting to acquire lottery picks is "misery," dealt two first-round picks to add point guard Goran Dragic at this season's trade deadline.

"Well, I don't think there's any doubt that if he stayed here, we would be the best team in the East, with what I had planned," Riley said. "You know, I don't think there's any doubt... But he didn't. So you'll never know. And I can't read his mind. Don't want to read his mind.

"I haven't really given it a whole lot of thought since then. For about a month. But I moved on. Because you have to move on. If you don't, you get truly left behind. And we had too much good here that we had built up—we still had Chris and we had Dwyane—we had these good players and we had some young players."

He set out to add a playmaker at the trade deadline to complement them, as well as the franchise find Hassan Whiteside ("Everybody knew who he was; it's just we were the first ones to say yes"), and successfully did so by landing Dragic, third-team All-NBA last season, for two first-round picks that Riley didn't want to wait to use, preferring "to get one step ahead of the posse with a great point guard." He expects to add more help next summer, "and the next move is 2016. I think this team in the next couple of years can get back to being the best team in the Eastern Conference."

Some may doubt him, but not in South Florida. Typically when a franchise loses a star half as special as James, the front office feels some heat. Instead, fans have rallied behind him, still labeling him "The Godfather" and creating #InRilesWeTrust hashtags.

Riley has seen his stature rise in the Miami area after the departure of LeBron James last summer.

He said he feels "honored and absolutely respected in this town," crediting it to longevity, and how "somewhere along the way, down the road, when you're about ready to turn a certain age, people will give you that kind of respect and honor, as I would give them. It has been predicated on 20 years of what I think they think has been good. They look at the franchise as a franchise that really wants to win and competes to win. Micky is the driving force behind that, and it's my job to try to go out and try to make things happen."

No matter how many bad things happen. Lately, many have been beyond his control, and gone beyond basketball. One common misconception is that he's cold, calculating, cut-throat. In truth, he's sentimental.

"Very much so," Riley said. "Back in the day, I was a letter writer. Because we didn't text. And didn't have a cellphone. Didn't have emails. There probably were emails, I just wasn't into it."

For a while, he also used to give out laminated "Forever" cards to favorites or soon-to-be favorites.

Players, like Dragic, now get a new one.

It reads:

"I know who you think I am. I can't make promises! But I will show you I am different."

If that wasn't evident when he closed his Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame speech by quoting Bruce Springsteen's "Back in Your Arms Again" to his wife, whom he lovingly calls "the quintessential basketball lifer from a spousal standpoint," or when he gushes about his two kids who have now left the nest, it comes across when he revisits his relationships with former players.

Those relationships can be tricky at times. He long ago adopted a philosophy espoused by author Robert Keidel that, in Riley's words, "the hardest thing to do as a coach or as a manager or as a president is to get players to do the things they don't want to do in order to achieve what they want. And the objective of the player and his agent is for us to do everything that we don't want to do to help him. And this is great. Because what he talks about is there must be a tension, a nice tension that's ongoing that doesn't create crisis but where you can collaborate with both sides....Because that's what creates an edge."

Riley conceded that, as a driver and motivator, he has created a lot of tension with players, but believes that while some disliked him, and maybe "still can't get over getting yelled at," he feels great respect from plenty of others.

"I think the only thing a coach would want from his players is that when you see them years later, you give each other a hug," Riley said, before breaking into laughter. "Whatever happened between you and me, it was all for the wonderful cause of winning. That we both had the burning desire to do."

As he has with many of his longtime players, Riley forged a bond with Anthony Mason that was as much about family as it was the business of basketball.

Riley and Anthony Mason had their battles, but there was also much love, which made attending Mason's funeral last week so difficult. "When one of your players, that you coached very intensely for five years, leaves the planet before you do, it's like one of your children," Riley said. "It's just very hard."

He's been around long enough to see several other favorites—his Forever Men, from Brian Grant to Magic Johnson to Alonzo Mourning—endure serious health hardships. "When Earvin went down, we thought it was the worst," Riley said. "When Zo went down, we thought it was the worst. When Chris, you think it's the worst....So it really affects you."

The Bosh news was better than it could have been: The blood clots were caught, and he is expected to recover fully enough to play next season. Still, it brought back painful flashbacks of 2000, when Riley built a new contender around Mourning, only for Mourning to be diagnosed with kidney disease in training camp.

"Yes, it was the same, same thing," Riley said softly. "We'd worked for a couple of weeks thinking about all of these players that were going to be available."

Then, on March 19, he agreed to acquire Dragic from Phoenix.

"We didn't make the trade call until about 7:30," Riley said. "About 5:30, I got the call from [Dr.] Harlan [Selesnick], what Chris had. Even before the trade call, I knew, I didn't tell anybody, except I told Nick about it. And we were just stunned, absolutely just stunned. More concerned for his health, you know."

He recalled Udonis Haslem recovering from blood clots in his lungs four years earlier.

"So it gave me hope, and I think it gives Chris hope, that this is just healing, the right medication, rest, whatever he needs just to dissolve that, and get him healthy," Riley said. "But it was just another blow. It was a big blow to the franchise and to the fans of hope."

After the organization had, in his opinion, pulled itself "up by the bootstraps."

"And then you have to wait," he said. "So put it all in one little box; it was like a wasted year...you don't have that many years, so you don't want to waste any of them."

It's been nearly 48 years since his NBA beginning, with nine championships as either a player, assistant, head coach or executive.

What could possibly be left to prove?

He insisted there's nothing, not to others, nor to himself. He referenced a book called Passages by Gail Sheehy about how a person progresses through the decades: driven to excel and support oneself and one's family in the 20s and 30s, wanting to leave something sustainable once in the 60s—a decade he's leaving behind on March 20, though don't expect a grand public celebration of the occasion.

"My motivation is I still want to win," Riley said. "And I want to provide for Erik everything I can from what I know to what he's learning. And he's growing past me. He's on to another thing, he's the pulse of analytics and the threes and running and a lot of ball movement and all that stuff. We're right in the process of going through a transformation in how I used to coach and how he wants to play."

Riley said he's around for reinforcement, support.

"I'm not driven like I used to be," Riley said. "But I do want this organization to stay what it is. As long as it's on my sort of watch here, I still want to bring great success for Micky and for the fans. And I feel really bad right now, where we are, versus where we could be."

He is searching to recapture other feelings, like that which he had most recently when the Heat won the title in 2012 and 2013, and last as a coach in 2006. "You never forget 'em. But they're so fast," Riley said. "It's about 10 minutes of absolute euphoria for everybody. And your family is coming down from the stands. And everybody's on the court. And it's real. It's the most real moment in sports when you succeed together, and there's this incredible real emotion."

And if there's another?

"If we ever get to that point again when I'm still here, I will walk right out of the arena," Riley said, smiling. "Chris and I will just walk out of the arena. We will get in a car, we will go to the airport and we will go! There will be no need for a celebration or talking to ESPN about how great everything was....I might wait for the celebration in the locker room.

Riley says that he would likely retire if the Heat were able to win yet another NBA title.

"It's possible. And I think we are right on time with it over the next couple of years. We're good right now, but we're gonna get better."

That would end his run? For real?

He laughed.

"If we would ever win one, I would say probably that would," Riley said. "Definitely. I don't want to have to come back again and try to do it again. So there's always a perfect time. You don't know when that is. It's just like you don't know when you're gonna win one, and you don't know when that time is going to come, when you go, 'Hey, let's stop.' I've really had a blessed career, and I've been around great people."

Then quietly...

"I don't have one thing to complain about or ever regret."

Ethan Skolnick covers the NBA for Bleacher Report and is a co-host of NBA Sunday Tip, 9-11 a.m. ET on SiriusXM Bleacher Report Radio. Follow him on Twitter, @EthanJSkolnick.

No comments:

Post a Comment